SAWAKO GODA

Nonaka-Hill is proud to announce the representation of Sawako Goda (b. 1940 - d. 2016), a complex artist celebrated by the Japanese avant-garde during her remarkable 50 year career, yet virtually unknown in the United States. An expansive selection of her paintings, sketches and ephemera will be on exhibition at the Los Angeles gallery. The exhibition opens on February 15th from 6-8 pm and will be on view until April 5th, 2025.

Sawako Goda: The Story of the Eye

Text by Julian Myers-Szupinska

Born in 1940 in Kōchi Prefecture, Japan, the artist Sawako Goda traversed, in the first half of her life, many aspects of Japan’s inventive postwar avant-gardes. Precocious, she gained early attention in the mid-1960s for junk assemblages of materials collected on still-war-damaged streets, which she shaped into whimsical mutant dolls or spindly, inoperable home appliances webbed in twisted wire, simultaneously tarnished and bejeweled. Fun With Junk reads the title of Goda’s first book, published internationally in 1966. [1] Wind the clock half a decade forward and find the restless Goda living in New York City with her then-partner, Tomio Miki—an “Obsessional Artist” and a contemporary of Yayoi Kusama—and at a pivotal moment. On returning to Japan in 1971, she began painting with oils, drawing inspiration from old magazines and photographs found in a New York antique shop, [2] and from a precious book, the Museum of Modern Art’s catalogue of E. J. Bellocq’s Storyville Portraits, which depicted prostitutes in early 20th century New Orleans. [3]

Decadent, faded, surreal, seedy glamor became her central preoccupation; musician Lou Reed makes more than one appearance in her work in this period. [4] She painted prolifically, made illustrations for magazines and advertisements, and, over the course of the 1970s, designed stage sets and posters for underground theater troupes, including Jūrō Kara’s Jōkyō Gekijo (Situation Theater), and Tenjō Sajiki (Top Floor Gallery), a troupe led by the avant-garde poet and dramatist Shūji Terayama. Another pivot, in the late 1970s, found her embracing film mediums more directly, in the form of a now-lost film, Nightclubbing (1977), which borrows its title from an Iggy Pop song, [5] and Polaroid sequences such as Flower Child (1981), which assembled shimmering portraits with unblinking painted eyes.

Goda lived, over this period, in a high-rise in Wakabayashi, Setagaya, a ward southwest of Tokyo, and among other prominent artists and poets. [6] If her work stood out for its Western preoccupations—surrealist portraits of film icons Marlene Dietrich and Veronica Lake, tributes to Reed and Marcel Duchamp’s femme alter-ego Rrose Sélavy—she was nevertheless throughout this period woven tightly into a rich community of forward-thinking artists and was showing her work regularly. In the mid-1980s, however, this weave began, slowly then suddenly, to fray. [7] She became increasingly obsessed with a different fantasia, that of ancient Egypt. After a visit to Cairo with her two daughters in 1978, she decided to relocate her family there permanently in 1985—and not to one of the nation’s cosmopolitan cities, but to Gabal Takouk, a Nubian village on the Nile near the Aswan Dam.

The move proved less than permanent. Despite its beauty, the heat was intense, the village offered few work opportunities to foreigners, and the international mail system—which Goda, working as a contributor for Asahi Shimbun, required to send her work to Japan—was unreliable. [8] They returned to Japan after just a year. Yet the encounter with Egypt provoked a dramatic transformation in her life. She saw spacecraft and heard the voices of the dead, and her practice became increasingly visionary and abstract. Under the influence of ancient Egyptian iconography—particularly the Eye of Horus—she drew eyes with a renewed obsession, and with her camera sought out gelatinous eyeball-like globes everywhere in nature. [9] Borrowing from the Surrealist technique of automatic drawing, she produced scribbled abstractions with color pencils, at times avoiding the facility of her highly trained hand by drawing with pencils wedged between her toes. [10]

The eminences of Old Hollywood returned, as well, in new artworks that situated Lillian Gish and Pola Negri alongside Nefertiti, and often fixated on an isolated eye, sometimes with gem-like geometries emerging from their sclera. Where Goda’s 1970s portraits had embraced a color palette not far from German Expressionism—the unnatural greens of Ernst Kirchner or the deathly pallor of Otto Dix—Goda’s colors in the 1990s became more silvered, uncanny, and luminous, evoking inner vision and optical disability: monochromacy, blurring, and macular degeneration. [11] Indeed, Goda suffered persistent retinal problems after 2000 which blurred and distorted her vision, and eventually lost the use of her right eye; she produced notebooks of blind drawings around this time. [12]

One wonders idly if she might have encountered, around 1990, Vaughan Oliver’s Surrealist-influenced designs for the English record label 4AD, or the blurred aesthetics of the band My Bloody Valentine—maybe not. More apposite are the reflections of the American artist and postmodern critic Peter Halley, who wrote in his 1984 essay “The Frozen Land” of the “culture of old movies” in an endlessly mediatized world, which produces an “asynchronic present” in which actors from the past persist forever in varied celluloid simulacra: as children, adults, and corpses. [13] “Is Shirley Temple a child or a woman? Is Lauren Bacall twenty or sixty years old?” he wondered. [14] This postmodern necropolis, Halley says, also enacts a paradoxical denial of death. One is reminded again of ancient Egypt, which had its own approach to eternity mediated through an insistence on preserving the faces of the iconic dead forever. There is, in other words, a shock when one encounters Goda’s portraits of living actresses like Helena Bonham Carter or Isabelle Adjani; they seem too present, too alive, to belong to Goda’s cinematic afterlife with Gish and Greta Garbo.

To call the artworks that Goda produced in her last two decades only “ghostly” or “deathly,” however, is to take things too far. She was equally transfixed by life: the curled whiskers of a beloved cat, flower buds and blooms, and, everywhere, ovoid shapes—eggs. As the Surrealist Georges Bataille intuited in his 1928 novella The Story of the Eye, the eyeball and the egg are uncanny proxies (and, in Bataille’s scandalous telling, both open the way toward orgasm). [15] Goda’s story of the eye is also full of eggs, from as early as the psychedelic egg-forms she made in the late-1960s and reaching apotheosis in her final decades. Eggs invoke creation and new life: yolks rupture and flow; buds burst into flowers that re-enact the creation of the world; eyeballs rupture like stars into colorful, gaseous nebulae. In other words, Goda’s eyeballs always want to hatch—to birth otherness. And, subject to the desiring gaze, each of her beloved actresses could also parse as just this sort of bud-egg-eye. Their fullness embodies the possibility that the death-life of cinema might rupture, and then flower, into something like another world.

In the last decades of Goda’s life, she lived in Kamakura, a seaside city south of Tokyo that she initially scorned, in her daughter Nobuyo’s telling, as embodying a “stereotypical image of Japan”—something Goda’s proclivity for otherness disposed her to resist. [16] Kamakura’s remove, however, came to suit her in a different way, by allowing her work to spool out according to its inner needs: its visionary, rather than social, logic. This separateness had consequences. Arguably it licensed scholars to omit her work from most surveys of postwar Japanese art. [17] Likewise, Goda’s 2003 retrospective at the Shoto Museum of Art consolidated a narrative of her life as a charismatic outsider who worked “more or less independently of the major trends in the art world.” [18] Maybe her work, with its Western references, was seen as not Japanese enough? Goda’s work exposes the brittleness of these containments; like eggshells, they break, spilling cosmic light and gooey yolk.

[1] Sawako Goda, Fun with Junk: Making Funny Figures Out of Odds and Ends, with photographs by Yoshikatsu Saeki (New York: Crown Publishers, 1966).

[2] Yuri Mitsuda, “Sawako Goda – Schattenbild (Silhouette),” in Sawako Goda: Schattenbild, 1958–2003, ed. Yuri Mitsuda (Tokyo: The Shoto Museum of Art, 2003), 198. Mitsuda argues that Goda was among the first Japanese artists to reproduce a photograph in paint and links her work with that of Gerhard Richter and Jiro Takamatsu (199).

[3] An exhibition of photographer E. J. Bellocq’s Storyville Portraits, directed by the Museum of Modern Art’s curator of photography John Szarkowski and printed from original negatives by the photographer Lee Friedlander, appeared at the museum from November 19, 1970–January 10, 1971. It is unclear if Goda could have seen the exhibition in person, but the catalogue (E. J. Bellocq: Storyville Portraits: Photographs from the New Orleans Red Light District, circa 1912, ed. John Szarkowski (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1971)) appears in an informal photograph of the artist and a friend, misdated 1969, in Goda Sawako: A Retrospective, ed. Ayumu Hirose and Hiromi Yanagisawa (Kyoto: Seigensha Publishing, 2022), 121. The arrangement and subject of Goda’s early painting Bed(1971) was likely influenced by Bellocq’s photographs.

[4] These include a painting and drawing modeled on press photographs of Reed, and a painting derived from the back cover of his album Transformer (Lou Reed, Transformer, recorded at Trident, London (August 1972; New York: RCA Victor LSP 4807, 1972), vinyl LP). Yuri Mitsuda notes pithily that Goda’s work in this period “smells of subculture” (Mitsuda, 197) and Goda’s paintings, including her riff on the back cover of Transformer, appeared on the covers of Rock Magazine (Japan), 1976–77.

[5] The song “Nightclubbing” appears on Iggy Pop, The Idiot, recorded August 1976 at Musicland Studios, Munich (1976; New York: RCA Victor APL1 2275, 1977). Assigned the same year as The Idiot’s release, Goda’s title suggests she was following the musician closely; a surviving Polaroid sequence from Nightclubbing is dated December 1977.

[6] Interview with Nobuyo Goda, the artist’s daughter, 2017.

[7] By the mid-1980s, Mitsuda writes, “the smell of burnt ruins had been swept away in Japan, student movements and political struggles had faded out, ‘avant-garde’ art had already left the scene, and the meaning of ‘underground’ theater had changed.” Mitsuda, 200.

[8] Goda’s illustrated diaries appeared in Asahi Shimbun in thirty-one installments, January 3–August 8, 1986, under the title “Nile no yuhi wa hanjuku tamago—Goda Sawako Egypt nikki” . These diaries were later collected as a book, By the Side of the Nile (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun, 1987).

[9] Goda: “In the process of taking pictures with a close-range lens, I realized that everything has eyes.” Quoted in Mitsuda, 201. Goda’s eye-focused book A Harem of Eyes (Tokyo: PARCO Shuppan, 1988) summarizes her experience in Egypt.

[10] “Chronology,” in Sawako Goda: Schattenbild, 196

[11] In ancient Egyptian mythography, Horus’s eye was torn out by his rival Set and was regenerated magically. As such, the Eye of Horus was seen as a symbol of protection, healing, and regeneration.

[12] Mitsuda, 202.

[13] Peter Halley, “The Frozen Land,” in Collected Essays 1981–1987 (Zürich and New York: Bruno Bischofberger Gallery and Sonnabend Gallery, 1988), 126.

[14] Halley.

[15] Georges Bataille, The Story of the Eye, trans. Joachim Neugroschel (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1987; originally written in French under the pseudonym Lord Auch, Histoire d’oeil, 1928).

[16] Nobuyo Goda, 2017.

[17] See, for example, Alexandra Munroe, Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1994), or Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde, ed. Doryun Chong (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012); neither mentions Goda’s work.

[18] Mari Tsukamoto, curator at the Museum of Art, Kōchi, dismantles this assertion effectively in “Who’s Watching Who? The Art of Goda Sawako,” in Goda Sawako: A Retrospective, 163–69.

Sawako GodaQueen of the Requiem Hiroshima 鎮魂 の 王妃 ヒロシマ, 2006Oil on canvas, framed37 3/8 x 17 3/4 in

Sawako GodaQueen of the Requiem Hiroshima 鎮魂 の 王妃 ヒロシマ, 2006Oil on canvas, framed37 3/8 x 17 3/4 in

95 x 45 cm Sawako GodaLa Bohème (Lillian Gish), 1994Oil on canvas, framed35 7/8 x 24 1/8 in (91.2 x 61.2 cm)

Sawako GodaLa Bohème (Lillian Gish), 1994Oil on canvas, framed35 7/8 x 24 1/8 in (91.2 x 61.2 cm) Sawako GodaMother Ship 母船, 1996Oil on canvas, framed46 x 35 7/8 in (116.7 x 91 cm)

Sawako GodaMother Ship 母船, 1996Oil on canvas, framed46 x 35 7/8 in (116.7 x 91 cm) Sawako GodaBoy's Head, 1979Oil on canvas, framed17 3/4 x 24 in (45.2 x 60.8 cm)

Sawako GodaBoy's Head, 1979Oil on canvas, framed17 3/4 x 24 in (45.2 x 60.8 cm) Sawako GodaPainting for the advertisement of Prince Lighter プリンスライター, n.d.Oil on canvas35 7/8 x 25 5/8 in (91 x 65.2 cm)

Sawako GodaPainting for the advertisement of Prince Lighter プリンスライター, n.d.Oil on canvas35 7/8 x 25 5/8 in (91 x 65.2 cm) Sawako GodaPrince Lighter プリンスライター, n.d.Oil on canvas46 x 31 5/8 in (116.7 x 80.3 cm)

Sawako GodaPrince Lighter プリンスライター, n.d.Oil on canvas46 x 31 5/8 in (116.7 x 80.3 cm) Sawako GodaA Green Look 緑 の ま な ざ し, 1994Oil on canvas, framed17 7/8 x 25 5/8 in (45.5 x 65.2 cm)

Sawako GodaA Green Look 緑 の ま な ざ し, 1994Oil on canvas, framed17 7/8 x 25 5/8 in (45.5 x 65.2 cm) Sawako GodaMarlene Dietrich (crystal eyes) マレーネ・デートリッヒ (クリスタルの目), 1994Oil on canvas, framed7 x 5 1/2 in (18 x 14 cm)

Sawako GodaMarlene Dietrich (crystal eyes) マレーネ・デートリッヒ (クリスタルの目), 1994Oil on canvas, framed7 x 5 1/2 in (18 x 14 cm) Sawako GodaMissing Person, 1997Oil on canvas, framed35 7/8 x 46 in (91.1 x 116.7 cm)

Sawako GodaMissing Person, 1997Oil on canvas, framed35 7/8 x 46 in (91.1 x 116.7 cm) Sawako GodaAnnabella アンナベラ, 1989Oil on canvas, framed12 1/2 x 16 1/8 in (31.8 x 41 cm)

Sawako GodaAnnabella アンナベラ, 1989Oil on canvas, framed12 1/2 x 16 1/8 in (31.8 x 41 cm) Sawako GodaIsis (Young Garbo) イシス( 若 き ガ ル ボ ), 1997Oil on canvas16 1/8 x 12 1/2 in (41 x 31.8 cm)

Sawako GodaIsis (Young Garbo) イシス( 若 き ガ ル ボ ), 1997Oil on canvas16 1/8 x 12 1/2 in (41 x 31.8 cm) Sawako GodaLaughing Child (3) 笑う子 供 (3), 2010Oil on canvas, framed16 1/8 x 20 7/8 in (41 x 53 cm)

Sawako GodaLaughing Child (3) 笑う子 供 (3), 2010Oil on canvas, framed16 1/8 x 20 7/8 in (41 x 53 cm) Sawako GodaMorse Code モールス 信号, 2000Oil on canvas, framed12 1/2 x 16 1/8 in (31.8 x 41 cm)

Sawako GodaMorse Code モールス 信号, 2000Oil on canvas, framed12 1/2 x 16 1/8 in (31.8 x 41 cm) Sawako GodaPermanent, 1997Oil on canvas17 7/8 x 15 in

Sawako GodaPermanent, 1997Oil on canvas17 7/8 x 15 in

45.5 x 38 cm Sawako GodaPromise, 1997Oil on canvas, framed40 1/8 x 25 3/4 in

Sawako GodaPromise, 1997Oil on canvas, framed40 1/8 x 25 3/4 in

102 x 65.4 cm Sawako GodaPurple Egg and Garbo 紫卵 の ガ ル ボ, 1995Oil on canvas, framed20 7/8 x 17 7/8 in (53 x 45.5 cm)

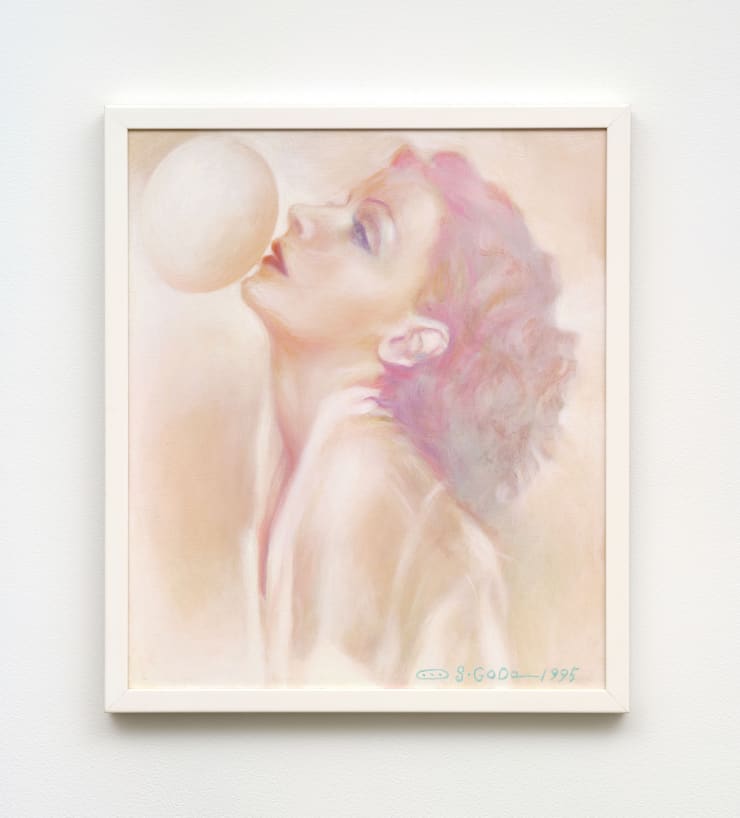

Sawako GodaPurple Egg and Garbo 紫卵 の ガ ル ボ, 1995Oil on canvas, framed20 7/8 x 17 7/8 in (53 x 45.5 cm) Sawako GodaUntitled タイトル無し, 1995Oil on canvas, framed20 7/8 x 17 7/8 in (53 x 45.5 cm)

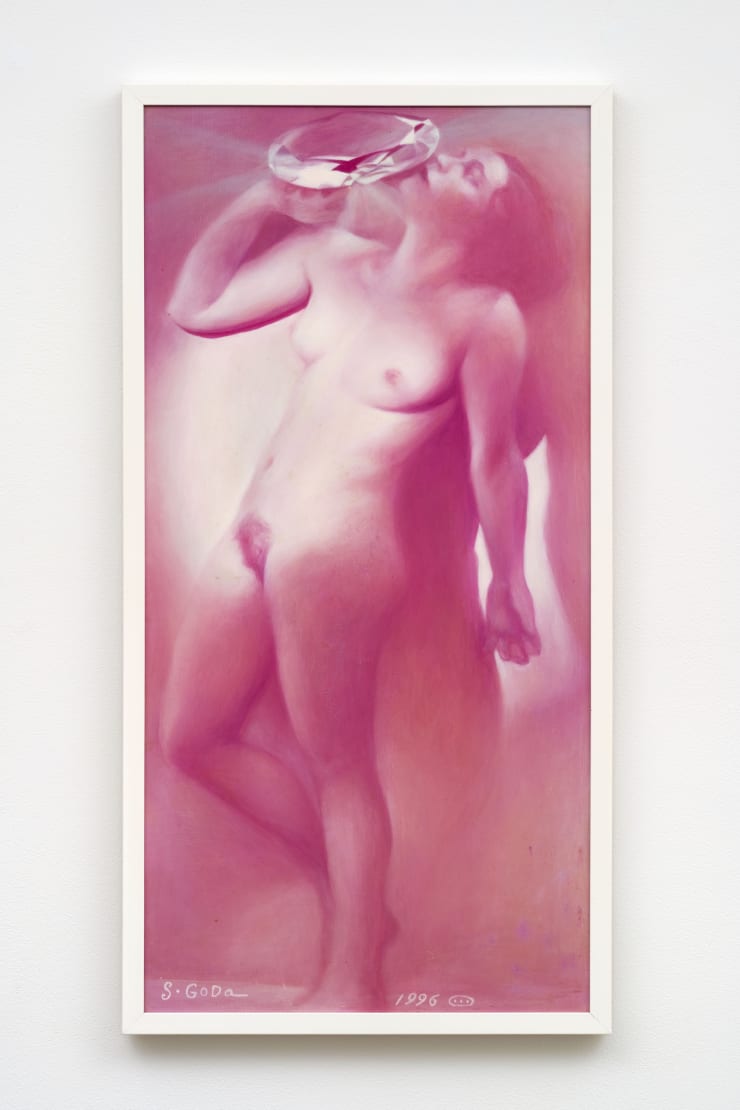

Sawako GodaUntitled タイトル無し, 1995Oil on canvas, framed20 7/8 x 17 7/8 in (53 x 45.5 cm) Sawako GodaViolet Nude バイオレットなヌード, 1996Oil on canvas, framed35 3/8 x 17 3/4 in (90 x 45 cm)

Sawako GodaViolet Nude バイオレットなヌード, 1996Oil on canvas, framed35 3/8 x 17 3/4 in (90 x 45 cm) Sawako GodaViolet Nude バイオレットなヌード, 1996Oil on canvas, framed35 3/8 x 17 3/4 in (90 x 45 cm)

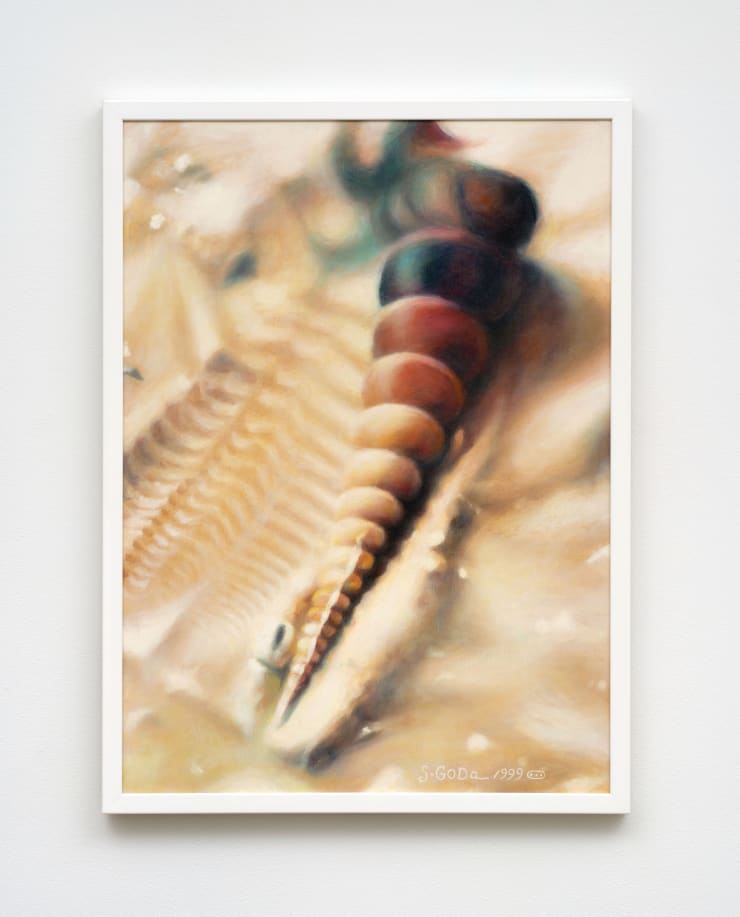

Sawako GodaViolet Nude バイオレットなヌード, 1996Oil on canvas, framed35 3/8 x 17 3/4 in (90 x 45 cm) Sawako GodaA Walk of the Sea Shell 巻き 貝 の 散歩 , 1999Oil on canvas, framed28 5/8 x 20 7/8 in (72.7 x 53 cm)

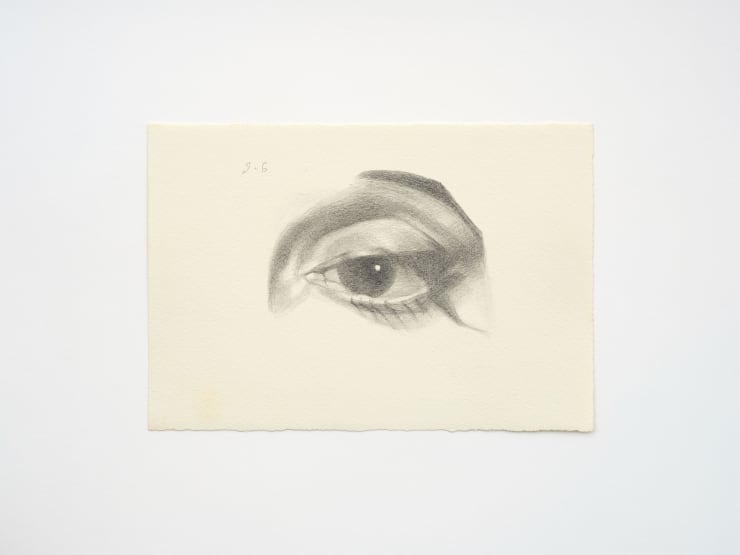

Sawako GodaA Walk of the Sea Shell 巻き 貝 の 散歩 , 1999Oil on canvas, framed28 5/8 x 20 7/8 in (72.7 x 53 cm) Sawako GodaJoan Crawford, 1990Pencil on paper えんぴつ/紙5 3/8 x 7 3/4 in (13.6 x 19.8 cm)

Sawako GodaJoan Crawford, 1990Pencil on paper えんぴつ/紙5 3/8 x 7 3/4 in (13.6 x 19.8 cm) Sawako GodaUntitled, 1991Pencil on paper えんぴつ/紙5 3/8 x 7 3/4 in (13.6 x 19.8 cm)

Sawako GodaUntitled, 1991Pencil on paper えんぴつ/紙5 3/8 x 7 3/4 in (13.6 x 19.8 cm) Sawako GodaHedy Lamarr, 1991Pencil on paper えんぴつ/紙5 3/8 x 7 3/4 in (13.6 x 19.8 cm)

Sawako GodaHedy Lamarr, 1991Pencil on paper えんぴつ/紙5 3/8 x 7 3/4 in (13.6 x 19.8 cm) Sawako GodaArletty, 1991Pencil on paper えんぴつ/紙5 3/8 x 7 3/4 in (13.6 x 19.8 cm)

Sawako GodaArletty, 1991Pencil on paper えんぴつ/紙5 3/8 x 7 3/4 in (13.6 x 19.8 cm) Sawako GodaAutomatism series オートマティズムシリーズ Toe Sensation 足の指のセンセーション, 1991Pastel crayon on paper クレパス/紙5 x 4 in

Sawako GodaAutomatism series オートマティズムシリーズ Toe Sensation 足の指のセンセーション, 1991Pastel crayon on paper クレパス/紙5 x 4 in

12.7 x 10.2 cm Sawako GodaAutomatism series オートマティズムシリーズ Toe Sensation 足の指のセンセーション, 1991Pastel crayon on paper クレパス/紙7 3/4 x 5 3/8 in

Sawako GodaAutomatism series オートマティズムシリーズ Toe Sensation 足の指のセンセーション, 1991Pastel crayon on paper クレパス/紙7 3/4 x 5 3/8 in

19.8 x 13.8 cm

Related artist

Artist Exhibited:

Ulala Imai

Kazuo Kadonaga

Kentaro Kawabata

Zenzaburo Kojima

Kisho Kurokawa

Tadaaki Kuwayama

Toshio Matsumoto

Keita Matsunaga

Yutaka Matsuzawa

Kimiyo Mishima

Kunié Sugiura

Takuro Tamayama

Tiger Tateishi

Sofu Teshigahara

Shomei Tomatsu

Wataru Tominaga

Hosai Matsubayashi XVI

Kansuke Yamamoto

Masaomi Yasunaga

Exhibitions:

-2025-

Chimeras: Sawako Goda and Kentaro Kawabata

Sea of Mud, Wall of Flame: Satoru Hoshino and Masaomi Ysunaga

KEY HIRAGA: The Elegant Life of Mr. H

-2024-

KYOKO IDETSU: What can an ideology do for me?

KENTARO KAWABATA / BRUCE NAUMAN

SAORI (MADOKORO) AKUTAGAWA: CENTENARIA

Keita Matsunaga : Accumulation Flow

-2023-

NONAKA-HILL ♥ TATAMI ANTIQUES: A holiday sale of unique objects from Japan

TAKASHI HOMMA : REVOLUTION No.9 / Camera Obscura Studies

TATSUMI HIJIKATA THE LAST BUTOH: Photographs by Yasuo Kuroda

Kiyomizu Rokubey VIII: CERAMIC SIGHT

Masaomi Yasunaga: 石拾いからの発見 / discoveries from picking up stones

SHUZO AZUCHI GULLIVER ‘Synogenesis’

Koichi Enomoto: Against the day

Tatsuo Ikeda / Michael E. Smith

Hiroshi Sugito: the garden with Zenzaburo Kojima

Zenzaburo Kojima: This very green

Tomohisa Obana: To see the rainbow at night, I must make it myself

Daisuke Fukunaga: Beautiful Work

- 2021 -

Natsuyasumi: In the Beginning Was Love

Takashi Homma: mushrooms from the forest

– 2020 –

Hosai Matsubayashi XVI & Trevor Shimizu

Sterling Ruby and Masaomi Yasunaga

– 2019 –

A show about an architectural monograph

Yutaka Matsuzawa

Yutaka Matsuzawa through the lens of Mitsutoshi Hanaga

Takuro Tamayama & Tiger Tateishi

Kunié Sugiura

Masaomi Yasunaga

Miho Dohi

Wataru Tominaga

Naotaka Hiro

Parergon: Japanese Art of the 1980s and 1990s

Tadaaki Kuwayama

– 2018 –

Toshio Matsumoto

Kentaro Kawabata

Kansuke Yamamoto

Kazuo Kadonaga: Wood / Paper / Bamboo / Glass

Press:

-2025-

OCULA, Kaoru Ueda

Galerie, Kaoru Ueda

Ceramic Now, Satoru Hoshino and Masaomi Yasunaga

ARTFORUM, Sawako Goda

Artillery Magazine, Sawako Goda

-2024-

Artsy, Nonaka-Hill

Richesse, Nonaka-Hill Kyoto

Bijutsutecho, Nonaka-Hill Kyoto

The Art Newspaper, Nonaka-Hill Kyoto

Meer, Kyoko Idetsu

Bijyutsutecho, Masaomi Yasunaga

Switch, Masaomi Yasunaga

ARTnews JAPAN, Masaomi Yasunaga

Richesse, Masaomi Yasunaga

Art Basel, Daisuke Fukunaga, Imai Ulala

Art Basel, Kazuo Kadonaga, Sofu Teshigahara

-2023-

ADF webmagazine, Yasuo Kuroda, Tatsumi Hijikata

e-flux, Sanya Kantarofsky, Yasuo Kuroda

Los Angeles Times, Kenzi Shiokava

Artillery, Masaomi Yasunaga

Contemporary Art Daily Shuzo Azuchi Gulliver

- 2022 -

Contemporary Art Daily, Tomohisa Obana

ARTE FUSE, Daisuke Fukunaga

Contemporary Art Daily, Daisuke Fukunaga

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles (Carla), Daisuke Fukunaga

What's on Los Angeles, Daisuke Fukunaga

Hyperallergic, Daisuke Fukunaga

Artillery, Kentaro Kawabata

Larchmont Buzz, entaro Kawabata

- 2021 -

Art Viewer, Natsuyasumi: In the Beginning Was Love

Hyperallergic, Natsuyasumi: In the Beginning Was Love

Art Viewer, Takashi Homma

Hyperallergic, Busy Work at Home

Art Viewer, Busy Work at Home

Hyperallergic, Ulala Imai

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles (Carla), Ulala Imai

Contemporary Art Daily, Ulala Imai

artillery, Ulala Imai

Special Ops, Ulala Imai

Art Viewer, Ulala Imai

artillery, Matsubayashi & Trevor Shimizu

– 2020 –

Ceramic Now, Sterling Ryby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Hypebeast, Sterling Ryby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Art Viewer, Sterling Ruby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Air Mail, Sterling Ruby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Los Angeles Times, Kaz Oshiro

ArtnowLA, Kaz Oshiro

What's on Los Angeles, Kaz Oshiro

KCRW, Kaz Oshiro

Tique, Kaz Oshiro

Contemporary Art Daily, Kaz Oshiro

Art Viewer, Kaz Oshiro

Contemporary Art Daily, Sofu Teshigahara

Art Viewer, Sofu Teshigahara

KCRW, Sofu Tsshigahara

Hyperallergic, Nonaka-Hill

Los Angeles Times, Keita Matsunaga

– 2019 –

Los Angeles Times, Tatsumi Hijikata

Art Viewer, Tatsumi Hijikata, Eikoh Hosoe

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles, Tatsumi Hijikata, Eikoh Hosoe

ArtAsiaPacific, Yutaka Matsuzawa

Los Angeles Times, Tatsumi Hijikata

AUTRE, Tatsumi Hijikata, Eikoh Hosoe

Los Angeles Times, Nonaka-Hill

ARTFORUM, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

Art Viewer, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

KCRW, Nonaka-Hill

LA WEEKLY, Nonaka-Hill

AUTRE, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

ArtsuZe, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

ARTFORUM, Review: Tadaaki Kuwayama, Rakuko Naito

Art Viewer, Masaomi Yasunaga, Kunié Sugiura

Los Angeles Times, Masaomi Yasunaga

KQED, Tadaaki Kuwayama, Rakuko Naito

Contemporary Art Daily, Naotaka Hiro, Wataru Tominaga, Miho Dohi

Los Angeles Times, Miho Dohi

Los Angeles Review of Books, Miho Dohi

Bijutsu Techo, Naotaka Hiro, Wataru Tominaga, Miho Dohi

Art Viewer, Miho Dohi

Art & Object, Parergon

COOL HUNTING, Felix Art Fair

Art Viewer, Tadaaki Kuwayama

artnet news, Nonaka-Hill

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles (Carla), Tadaaki Kuwayama

– 2018 –

Art Viewer, Kentaro Kawabata

Contemporary Art Daily, Kazuo kadonaga

Los Angeles Times, Kazuo Kadonaga

ARTFORUM, Kazuo Kadonaga

Contemporary Art Daily, Shomei Tomatsu

KCRW, Kimiyo Mishima, Shomei Tomatsu

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Find out more about cookies.