Sofu Teshigahara

Press:

Contemporary Art Daily, March 28, 2020

Art Viewer, March 24, 2020

KCRW, February 25, 2020

Nonaka-Hill is pleased to present a solo exhibition of works by Sofu Teshigahara (1900-1979). The artist’s first exhibition in Los Angeles introduces a selection of rarely seen metal sculptures and calligraphic works produced from the 1950s to the 1970s. The artist was founder of the Sogetsu School of Ikebana (1927 – ongoing), which is recognized as having made a significant mark on the history of postwar Japanese art. A grand-scale ikebana work composed by Teshigahara’s direct Sogetsu student, ikebana-master Kaz Yokou Kitajima, Ikkyu Shihan Riji of Sogetsu School of Ikebana spans the exhibition spaces. In the gallery’s back room, vintage photographs by Ken Domon (1909-1990) of Teshigahara’s ikebana works are also on display. The exhibition is on view until March 28, 2020.

Sofu Teshigahara was born in Osaka in 1900. It was the Meiji Era, a period of industrialization and modernization when the Japanese government imposed a mandate to “eliminate old customs” and to “search for new knowledge throughout the world”. At the same time, counteractive initiatives rose to preserve Japanese aesthetics, folk arts and the nation’s prehistoric spirit. In this paradoxical cultural climate, Sofu’s father Wafu Teshigahara taught the centuries old formalities of ikebana, but while wearing a Western-style suit. Under his father’s direction, young Sofu trained in ikebana and calligraphy during childhood, excelled and was already teaching ikebana by the age of thirteen.

The artist’s teenage and formative years, from twelve to twenty-six years old, were spanned by the liberal and worldly Taisho Era (1912-1926), and it was in this culturally expansive time that Sofu developed a disdain for the formalities of traditional ikebana and set his ambitions towards a radicalized ikebana practice. In 1927, Teshigahara left his father’s school in Osaka and moved to Tokyo to establish his Sogetsu School of Ikebana (Sogetsu translates as: Grass moon). Very soon thereafter, he was making exhibitions with students. By 1931, he had become very well known for his avant-garde works, which disregarded symbolisms, transcended the scale of living-room “tokonoma” alcoves, and could be shown outdoors. Together with fellow ikebana artists, Houn Ohara and Yukio Nakagawa, an “avant-garde Ikebana movement” rose which deviated from conventional practices and resulted in its unprecedented and thriving popularity. These artists referred to their temporal floral arrangements as “Objet”, borrowing the term from French Surrealists and inviting contemplation of ikebana as sculpture. Teshigahara stated “I hope to demonstrate that it is possible to create expressions using anything” and believed that ikebana could be made by anyone anytime, anywhere, using any material. Through treating materials such as iron, stone, and wood as equivalent to flowers, Teshigahara served to liberate Ikebana from its restricted visual and material language, meanwhile forming an approach to a considerable sculptural practice.

Teshigahara, who had spent decades working with ephemeral materials and saw his sculptural ikebana efforts come and go, chose more lasting materials for his sculptural practice. Around 1955, he devised a method of overlaying carved wood forms with brass, bronze or lead sheets covering the wood entirely or partially. The result was a hybrid of the organic and manmade, which covered and accentuated the forms underneath.

Throughout his sculptural practice, Teshigahara worked in themes that had apparent associations with the Japanese heritage. As the art historian, Soichi Tominaga had proposed, Teshigahara’s references to traditional Japanese arts were not a regression to the past but injecting new life into tradition. On his visit to Teshigahara’s studio, Tapié praised Teshighara for the experimental savoir vivre as an artist in contrast to academic artists. Tapié favorably described his sculptures as evoking internal reverberances from ancient Japanese pantheistic culture. Uzume [ウズメ] (1960), on display in the gallery comes from Teshigahara’s Kojiki series made in in the 1960s. His continued fascination for Kojiki [古事記], an 8th century anthology of Japanese ancient myths and history stemmed from a young age, being introduced to the book by Japanese literary scholar, Shuzo Okuda. The tall column form “Tachi (sword)” from 1968 bears associations in Japan to safeguarding the country, or to risking one’s destiny.

In his book “Avant-Garde Art in Japan” (1962), French art critic Michel Tapié writes: “The master Sofu Teshigahara is one of the three or four great masters in the art of flower arrangement (the Ikebana schools are certainly the only essentially artistic schools in the world which know what structure is and what space is). Though ruling an empire comprising some thirty thousand teachers and about a million pupils, Teshigahara engages in a number of other activities — I was going to call them annexes. I regard him as one of the three or four greatest living sculptors, not only in Japan, but in the world.” Tapies, who came to Japan in 1957 seeking to familiarize himself with Japan’s avant-garde artists, is credited with identifying the Gutai artists and debuting their works overseas. Teshigahara exhibited in Gutai exhibitions and could be said to be driven by a similar ethos to “make something which has never been seen before”.

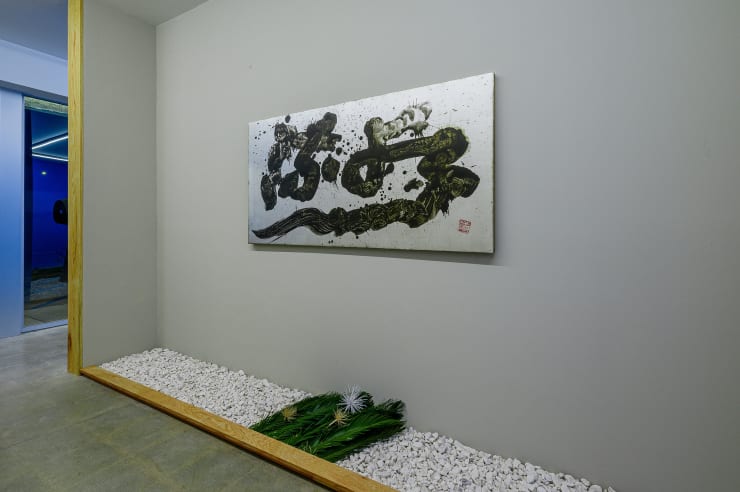

Calligraphy demonstrated Teshigahara’s speed and deliberation of the brush, producing works which are at once word, image and action. With his swift yet, dramatic black ink lines on paper, Teshigahara formed words associated with nature and mythology, often from everyday language. In the gallery corridor, the large-scale ink calligraphy, Ryusui (Flowing Water) [流水] (1977) evoke a dynamic landscape. Compositionally, the kanji are off-center, off-kilter, and at times brimming at the edges of the panel. Kanji is deconstructed in various degrees, at times essentialized to symbolic gestures of the word exemplified specifically in Gekko (moonlight) [月光], and Nichirin (Sun Rays) [日輪]. The vigorous brushwork unbound by convention echoes that of Teshigahara’s approaches to ikebana and sculptures.

Yet another aspect of Teshigahara’s legacy is the Sogetsu Art Center. As early as 1936, Teshigahara spoke with journalists about wanting Japan to have a museum for Modern Art and finally, in collaboration with his son Hiroshi, Sogetsu Art Center opened in the basement auditorium space of the Sogetsu Kai-an. Notable events include early performances by Yoko Ono (1962) John Cage and David Tudor (1962), Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s Japan performance (1964), and “20 Questions for Bob Rauschenberg” (1964), a legendary Q&A session while the artist composed an extraordinary Rauschenberg work on a gold folding screen in front of an audience. The Sogetsu school was rebuilt and opened in 1977 with a ground floor exhibition space designed by Isamu Noguchi. Art installations are frequently held in the space currently.

Sofu Teshigahara, at a very young age was nick-named “Little Teacher”, and it seems that he embodied a life-long leadership role in Japan’s post-war culture. In rapidly changing times, Teshigahara engaged his considerable gifts in the visual arts to adapt intrinsically Japanese aesthetics with vigor into his work, reflecting a more globalized condition. Teshigahara received numerous honors including, L'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, Officier (1960); French Legion of Honor, Chevalier (1961); and Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology’ s Art Encouragement Prize (1962). Sofu Teshigahara’s influence on Ikebana remains unparalleled as Sogetsu Schools of Ikebana continue to operate brances in several cities worldwide, led currently by Iemoto (Headmaster) Akene Teshigahara in Tokyo.

Currently, Sofu Teshigahara has a major sculpture on view in Paris at Foundation Louis Vuitton in the “Charlotte Perriand” exhibition.

Recommended viewing: Ikebana, 1956 By Hiroshi Teshigahara Color/sound. 32:29 minutes Japanese with English subtitles. Available on YouTube: “The history and art of ikebana, a centuries old Japanese art of flower arrangement and a look inside the Sogetsu School of Ikebana, where the director's father Sofu Teshigahara worked as the grand master of the school.”.

Sofu TeshigaharaTachi (Sword) , 1968Bronze98 7/8 x 21 5/8 x 15 in

Sofu TeshigaharaTachi (Sword) , 1968Bronze98 7/8 x 21 5/8 x 15 in

251 x 55 x 38 cm Sofu TeshigaharaTitle Unknown, 1950s-1970sWood, brass68 1/8 x 41 3/8 x 23 5/8 in

Sofu TeshigaharaTitle Unknown, 1950s-1970sWood, brass68 1/8 x 41 3/8 x 23 5/8 in

173 x 105 x 60 cm Sofu TeshigaharaTitle Unknown, 1969Bronze12 5/8 x 11 7/16 x 6 5/16 in

Sofu TeshigaharaTitle Unknown, 1969Bronze12 5/8 x 11 7/16 x 6 5/16 in

32 x 29 x 16 cm Sofu Teshigahara"Uzume" from "Kojiki" series, 1960Bronze.28 x 36-1/4 x 22 inches

Sofu Teshigahara"Uzume" from "Kojiki" series, 1960Bronze.28 x 36-1/4 x 22 inches

71 x 92 x 56 cm Sofu Teshigahara(title unknown), 1950s-1970sWood, brass.10-1/4 x 18-1/2 x 13 inches

Sofu Teshigahara(title unknown), 1950s-1970sWood, brass.10-1/4 x 18-1/2 x 13 inches

26 x 47 x 33 cm Sofu TeshigaharaNichirin, n.d.Hanging scroll, ink on paperPaper size: 36 5/8 x 24 11/16 in

Sofu TeshigaharaNichirin, n.d.Hanging scroll, ink on paperPaper size: 36 5/8 x 24 11/16 in

Scroll size: 80 1/2 x 33 1/8 x 1 1/4 in

Paper size: 92.9 x 62.6 cm

Scroll size: 204.5 x 84 x 3.2 cm Sofu TeshigaharaGekko, n.d.Hanging scroll, ink on paperPaper size: 17 7/16 x 23 9/16 in

Sofu TeshigaharaGekko, n.d.Hanging scroll, ink on paperPaper size: 17 7/16 x 23 9/16 in

Scroll size: 56 15/16 x 30 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Paper size: 44.2 x 59.8 cm

Scroll size: 144.6 x 76.8 x 3.1 cm Sofu TeshigaharaRyusui (流水), 1977India ink and silver foil on paper, on wood panel.35-3/4 x 68-7/8 inches

Sofu TeshigaharaRyusui (流水), 1977India ink and silver foil on paper, on wood panel.35-3/4 x 68-7/8 inches

90.8 x 175 cm Sofu TeshigaharaKumo (Clouds), n.d.Ink on paper14 15/16 x 17 7/8 in

Sofu TeshigaharaKumo (Clouds), n.d.Ink on paper14 15/16 x 17 7/8 in

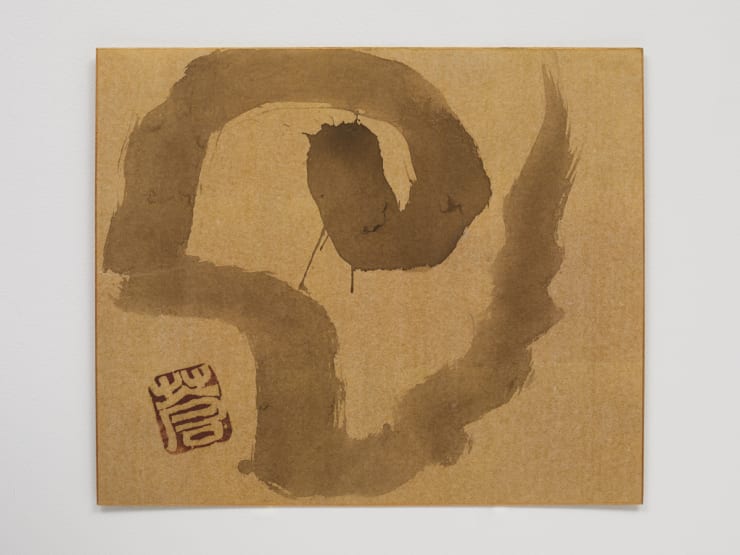

37.9 x 45.3 cm Sofu TeshigaharaMaboroshi (Phantom), n.d.Ink on paper mounted on boardPaper size: 12 x 15 5/8 in

Sofu TeshigaharaMaboroshi (Phantom), n.d.Ink on paper mounted on boardPaper size: 12 x 15 5/8 in

Board size: 16 11/16 x 20 1/4 x 3/4 in

Paper size: 30.5 x 39.6 cm

Board size: 42.3 x 51.4 x 1.8 cm Sofu TeshigaharaMaboroshi (Phantom), n.d.Ink on paper12 1/2 x 16 in

Sofu TeshigaharaMaboroshi (Phantom), n.d.Ink on paper12 1/2 x 16 in

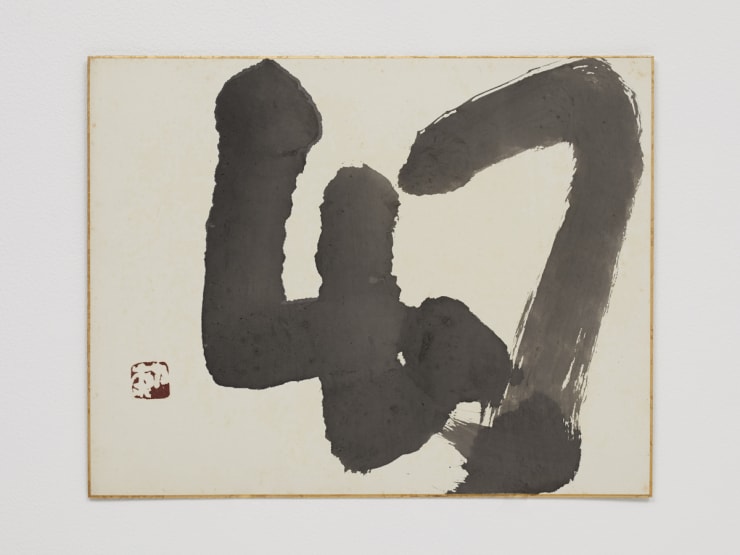

31.7 x 40.5 cm Sofu TeshigaharaShizen (Nature), n.d.Ink on paper14 15/16 x 17 7/8 in

Sofu TeshigaharaShizen (Nature), n.d.Ink on paper14 15/16 x 17 7/8 in

37.9 x 45.4 cm

Related artist

Artist Exhibited:

Ulala Imai

Kazuo Kadonaga

Kentaro Kawabata

Zenzaburo Kojima

Kisho Kurokawa

Tadaaki Kuwayama

Toshio Matsumoto

Keita Matsunaga

Yutaka Matsuzawa

Kimiyo Mishima

Kunié Sugiura

Takuro Tamayama

Tiger Tateishi

Sofu Teshigahara

Shomei Tomatsu

Wataru Tominaga

Hosai Matsubayashi XVI

Kansuke Yamamoto

Masaomi Yasunaga

Exhibitions:

-2025-

KEY HIRAGA: The Elegant Life of Mr. H

-2024-

KYOKO IDETSU: What can an ideology do for me?

KENTARO KAWABATA / BRUCE NAUMAN

SAORI (MADOKORO) AKUTAGAWA: CENTENARIA

Keita Matsunaga : Accumulation Flow

-2023-

NONAKA-HILL ♥ TATAMI ANTIQUES: A holiday sale of unique objects from Japan

TAKASHI HOMMA : REVOLUTION No.9 / Camera Obscura Studies

TATSUMI HIJIKATA THE LAST BUTOH: Photographs by Yasuo Kuroda

Kiyomizu Rokubey VIII: CERAMIC SIGHT

Masaomi Yasunaga: 石拾いからの発見 / discoveries from picking up stones

SHUZO AZUCHI GULLIVER ‘Synogenesis’

Koichi Enomoto: Against the day

Tatsuo Ikeda / Michael E. Smith

Hiroshi Sugito: the garden with Zenzaburo Kojima

Zenzaburo Kojima: This very green

Tomohisa Obana: To see the rainbow at night, I must make it myself

Daisuke Fukunaga: Beautiful Work

- 2021 -

Natsuyasumi: In the Beginning Was Love

Takashi Homma: mushrooms from the forest

– 2020 –

Hosai Matsubayashi XVI & Trevor Shimizu

Sterling Ruby and Masaomi Yasunaga

– 2019 –

A show about an architectural monograph

Yutaka Matsuzawa

Yutaka Matsuzawa through the lens of Mitsutoshi Hanaga

Takuro Tamayama & Tiger Tateishi

Kunié Sugiura

Masaomi Yasunaga

Miho Dohi

Wataru Tominaga

Naotaka Hiro

Parergon: Japanese Art of the 1980s and 1990s

Tadaaki Kuwayama

– 2018 –

Toshio Matsumoto

Kentaro Kawabata

Kansuke Yamamoto

Kazuo Kadonaga: Wood / Paper / Bamboo / Glass

Press:

-2025-

Artillery Magazine, Sawako Goda

-2024-

Artsy, Nonaka-Hill

Richesse, Nonaka-Hill Kyoto

Bijutsutecho, Nonaka-Hill Kyoto

The Art Newspaper, Nonaka-Hill Kyoto

Meer, Kyoko Idetsu

Bijyutsutecho, Masaomi Yasunaga

Switch, Masaomi Yasunaga

ARTnews JAPAN, Masaomi Yasunaga

Richesse, Masaomi Yasunaga

Art Basel, Daisuke Fukunaga, Imai Ulala

Art Basel, Kazuo Kadonaga, Sofu Teshigahara

-2023-

ADF webmagazine, Yasuo Kuroda, Tatsumi Hijikata

e-flux, Sanya Kantarofsky, Yasuo Kuroda

Los Angeles Times, Kenzi Shiokava

Artillery, Masaomi Yasunaga

Contemporary Art Daily Shuzo Azuchi Gulliver

- 2022 -

Contemporary Art Daily, Tomohisa Obana

ARTE FUSE, Daisuke Fukunaga

Contemporary Art Daily, Daisuke Fukunaga

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles (Carla), Daisuke Fukunaga

What's on Los Angeles, Daisuke Fukunaga

Hyperallergic, Daisuke Fukunaga

Artillery, Kentaro Kawabata

Larchmont Buzz, entaro Kawabata

- 2021 -

Art Viewer, Natsuyasumi: In the Beginning Was Love

Hyperallergic, Natsuyasumi: In the Beginning Was Love

Art Viewer, Takashi Homma

Hyperallergic, Busy Work at Home

Art Viewer, Busy Work at Home

Hyperallergic, Ulala Imai

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles (Carla), Ulala Imai

Contemporary Art Daily, Ulala Imai

artillery, Ulala Imai

Special Ops, Ulala Imai

Art Viewer, Ulala Imai

artillery, Matsubayashi & Trevor Shimizu

– 2020 –

Ceramic Now, Sterling Ryby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Hypebeast, Sterling Ryby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Art Viewer, Sterling Ruby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Air Mail, Sterling Ruby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Los Angeles Times, Kaz Oshiro

ArtnowLA, Kaz Oshiro

What's on Los Angeles, Kaz Oshiro

KCRW, Kaz Oshiro

Tique, Kaz Oshiro

Contemporary Art Daily, Kaz Oshiro

Art Viewer, Kaz Oshiro

Contemporary Art Daily, Sofu Teshigahara

Art Viewer, Sofu Teshigahara

KCRW, Sofu Tsshigahara

Hyperallergic, Nonaka-Hill

Los Angeles Times, Keita Matsunaga

– 2019 –

Los Angeles Times, Tatsumi Hijikata

Art Viewer, Tatsumi Hijikata, Eikoh Hosoe

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles, Tatsumi Hijikata, Eikoh Hosoe

ArtAsiaPacific, Yutaka Matsuzawa

Los Angeles Times, Tatsumi Hijikata

AUTRE, Tatsumi Hijikata, Eikoh Hosoe

Los Angeles Times, Nonaka-Hill

ARTFORUM, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

Art Viewer, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

KCRW, Nonaka-Hill

LA WEEKLY, Nonaka-Hill

AUTRE, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

ArtsuZe, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

ARTFORUM, Review: Tadaaki Kuwayama, Rakuko Naito

Art Viewer, Masaomi Yasunaga, Kunié Sugiura

Los Angeles Times, Masaomi Yasunaga

KQED, Tadaaki Kuwayama, Rakuko Naito

Contemporary Art Daily, Naotaka Hiro, Wataru Tominaga, Miho Dohi

Los Angeles Times, Miho Dohi

Los Angeles Review of Books, Miho Dohi

Bijutsu Techo, Naotaka Hiro, Wataru Tominaga, Miho Dohi

Art Viewer, Miho Dohi

Art & Object, Parergon

COOL HUNTING, Felix Art Fair

Art Viewer, Tadaaki Kuwayama

artnet news, Nonaka-Hill

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles (Carla), Tadaaki Kuwayama

– 2018 –

Art Viewer, Kentaro Kawabata

Contemporary Art Daily, Kazuo kadonaga

Los Angeles Times, Kazuo Kadonaga

ARTFORUM, Kazuo Kadonaga

Contemporary Art Daily, Shomei Tomatsu

KCRW, Kimiyo Mishima, Shomei Tomatsu

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Find out more about cookies.